“THINK BIG!”

Bode Museum, Berlin, DE

July 1st to October 31st

Egyptian tapestries from the Museum für Byzantinische Kunst’s rich textile collection are the source of inspiration for New York artist Gail Rothschild’s new series of monumental paintings. By juxtaposing her work with original ancient textiles from the 4th‒9th centuries, a fascinating dynamic emerges between the artifacts of a past culture and contemporary artistic production.

“Despite a deep respect for the historical exhibits and their history, it is important to Rothschild that visitors look at her works with joy, and certainly with humor.”

Read reviews of the show:

I was first introduced to the Bode Museum’s collection of Late Antique textiles on 21 March 2019 by Curator Cäcilia (Cilla) Fluck and Textile Conservator Kathrin Mälck. Now, in February 2022, as I reread our lively emails and photographs exchanged, I am grateful that our collaboration has grown into a warm friendship. Here in the US, I have more friends who have given advice; friends who also happen to be experts in Late Antique textiles. I meet with Art Historian Thelma Thomas of New York University every Sunday night—a high point of my week. Another friend, Elizabeth (Betsy) Došpel Williams, Assistant Curator of the Byzantine Collection at Dumbarton Oaks, provided intriguing insights. From the Metropolitan Museum, Textile Conservator Kathrin Colburn and Curator Helen Evans also gave guidance. And, of course, my studio manager, Sam Monaco, who, despite our new long-distance work situation, made it easy for me to focus on painting. In these studio notes, excerpts from correspondence, and conversations, I call my helpers by their first names.

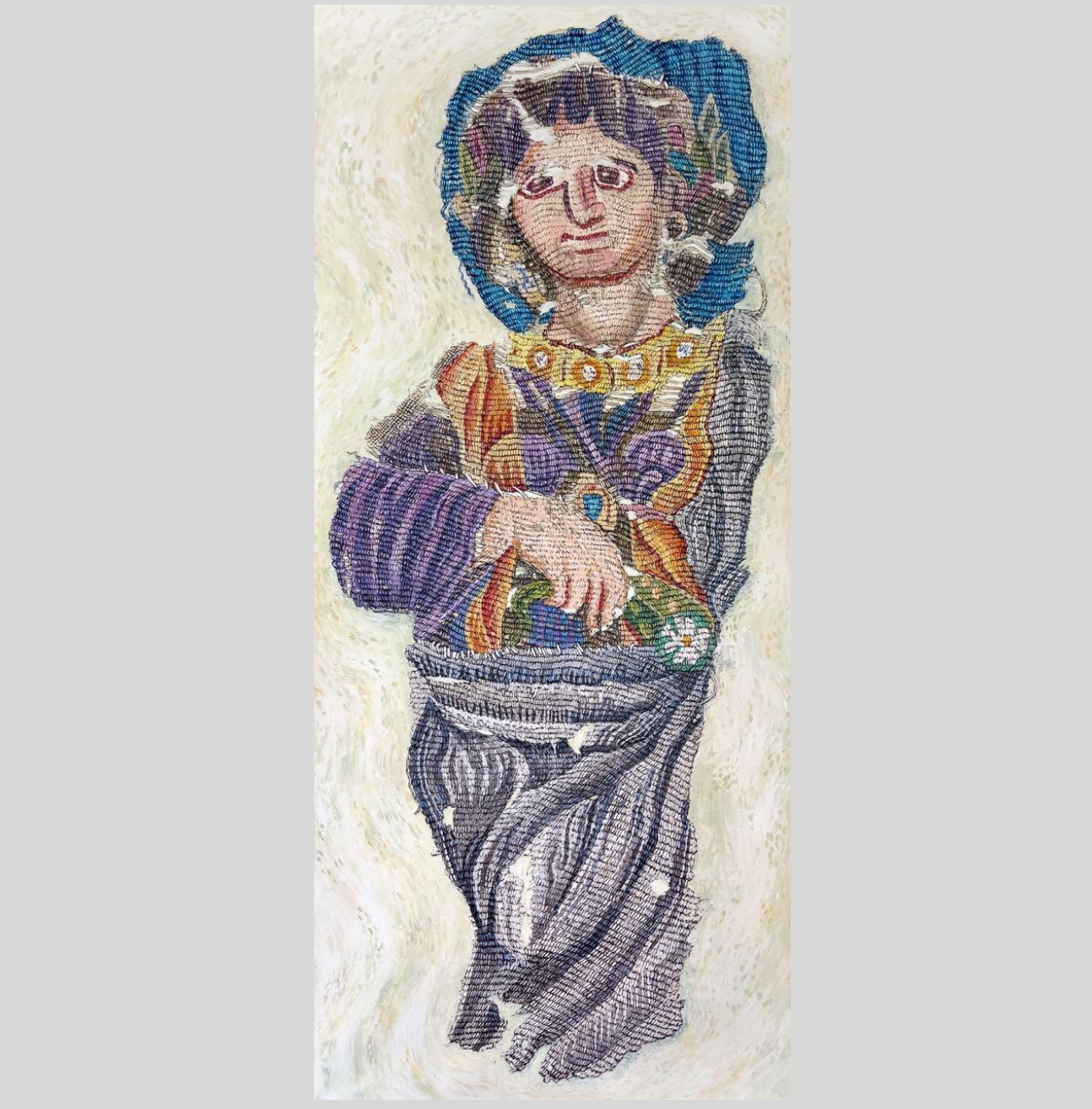

Renpet, 2019

Acrylic on canvas

79 ½ x 34 inches (202 x 86.5 cm)

Renpet: Snip snip, who clipped this lady out of the larger fabric she once was a part of? Did she decorate a curtain, blessing an Egyptian home with her serene—and now crooked—smile? These are things I ponder as I work. I must ask Cilla, as they are questions for an art historian. I look at the image on my paint-spattered iPad of a colorful lady swaddled (or is she shrouded?) in black and white. She seems to be missing feet. I paint the suturing stitches in her mid-section, wondering if they represent part of an earlier conservation effort, or is she an amalgam of two ancient fragments sewn together to please a 19th-century collector? Here in my Brooklyn studio, where a delivery truck has been idling beneath my window for the last hour, I focus on the object itself.

At the museum, Kathrin had described with such obvious affection the thread-by-thread repair of her treasured “Schätzchen.” Squeezing another blob of Dioxazine Purple onto my palette, I imagine that some 19th-century collector fell in love with her classical features, flowers, and fruit, seeing in her a Roman goddess like Flora or Ceres. I paint tiny brushstrokes around the perimeter of the figure, so she seems to swim through infinite space. In the Egyptian pantheon it was Renpet who personified fertility, spring, and youth. Taking another snapshot of the half-finished painting, I send it to Cilla and Kathrin in Berlin and confide that I sense them peeking over my shoulder. They reply, it feels like we’re weaving together. April sunlight streams across the canvas stapled to the wall like a specimen. Later the painting will be stretched, but for now Renpet can be rolled up and travel with me. Rennie, my Border Terrier, and Petra, my Golden

Retriever, dream happy dog-dreams. “Ren,” I yell, “Pet,” time for supper! Renpet has become my Schätzchen too.

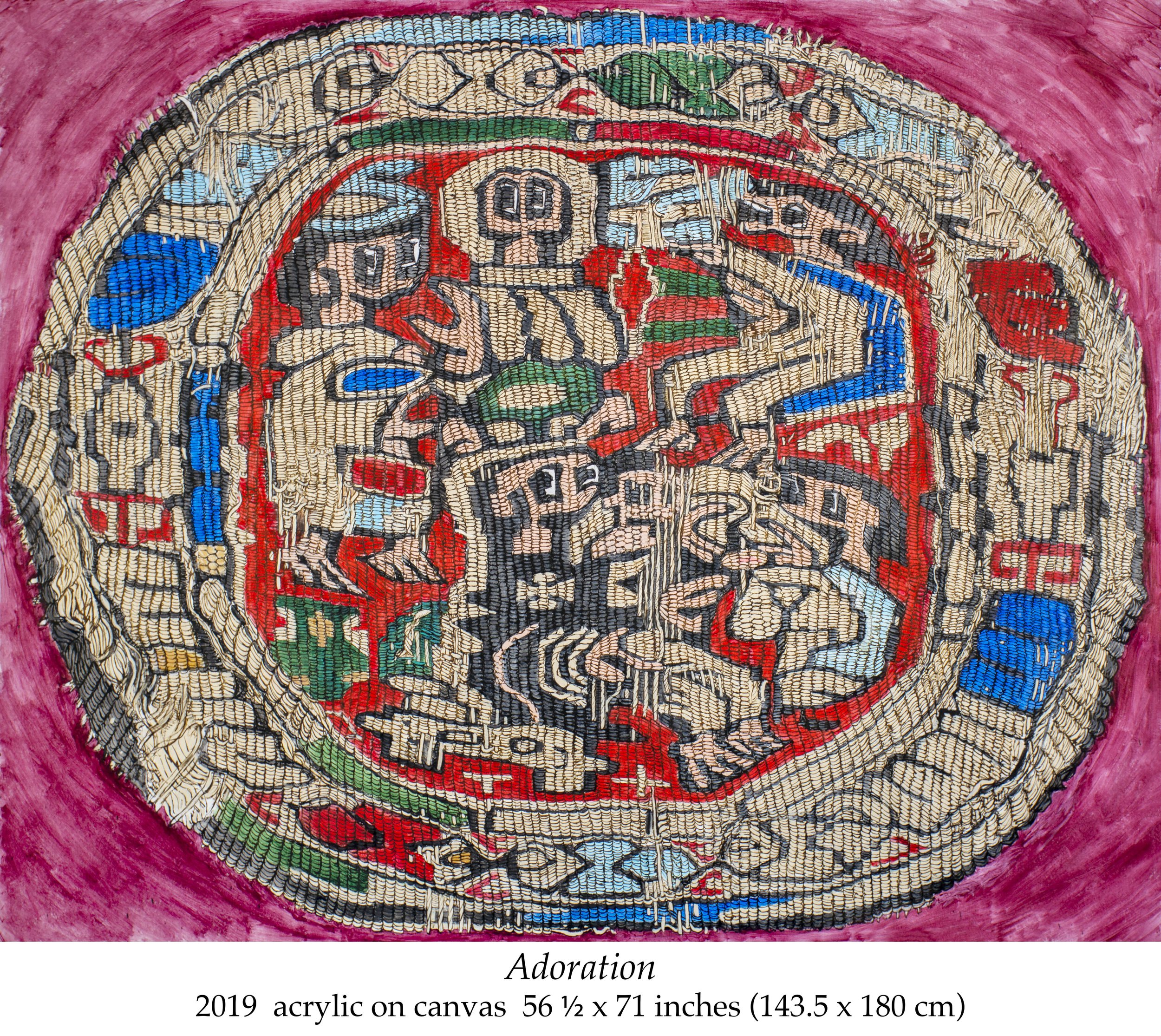

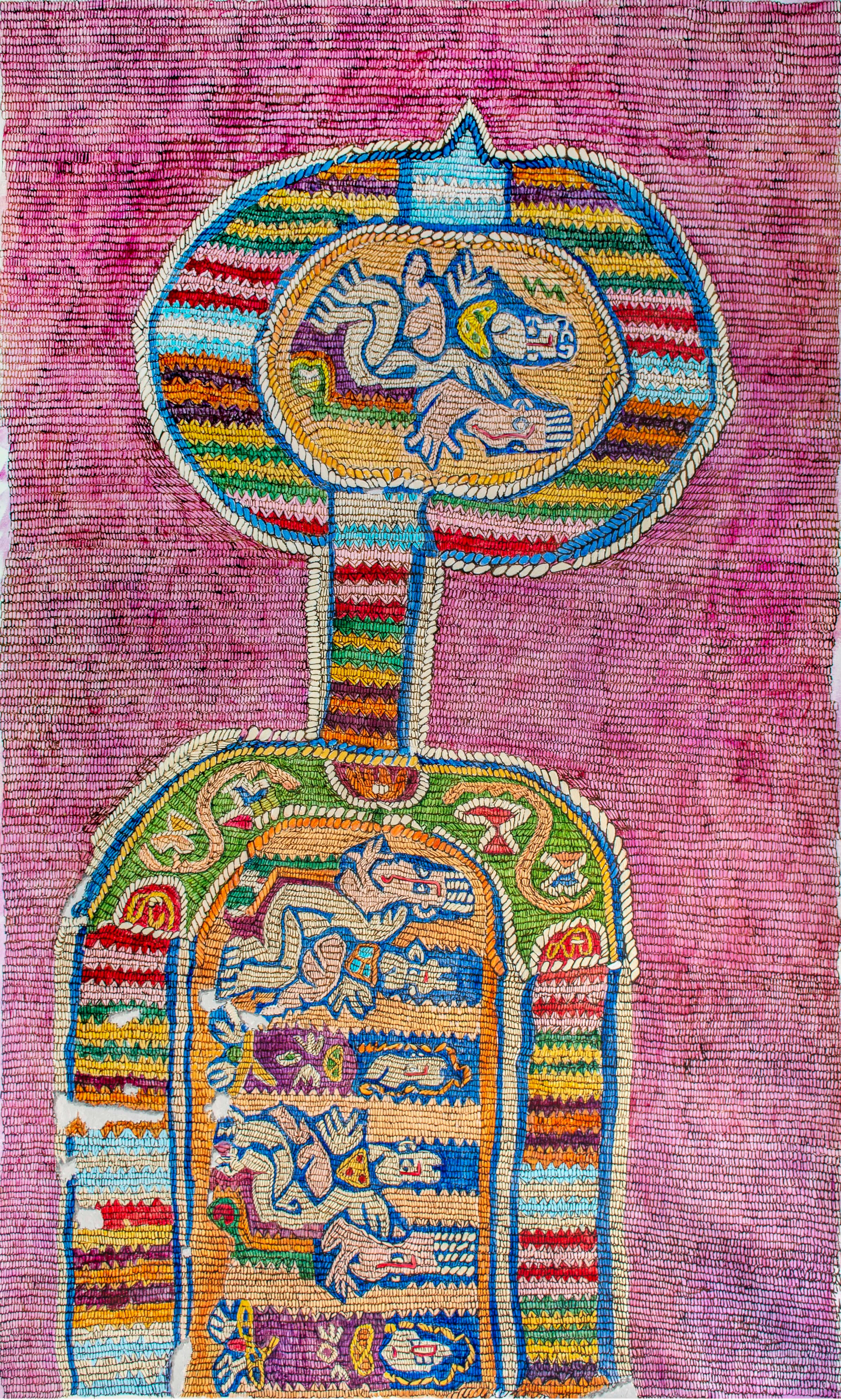

Adoration, 2019

Acrylic on canvas

57 x 70 inches (144.75 x 178 cm)

Adoration: The subject represented in this textile may be an Adoration, but what drew me to it was the delicious weirdness of the figures. Since the roundel was scissored from a tunic, any other decorations that might have completed the intended narrative have been lost. As I paint the three strange characters, I invent my own stories. Are they magi? I think the one on the left looks more like a lady from the 1950s, clutching her purse. I search for just the right red as rows of stitches become shadowed hills and valleys. Is it an image of Mother Mary and Baby Jesus? Or is it Mother Isis and Baby Horus? In Egypt of the early first millennium, any or sometimes multiple readings might be possible. What I respond to, however, is the object I see in its current condition. Thelma and the gang from the Metropolitan Museum come to Brooklyn to see how the work is progressing. I tell them the unraveling wool on the child’s face gives him a demonic look. He seems to be snatching at the offered gift saying, “Give me that.” Helen peers at the colorful shapes below the child where I have not yet painted individual stitches. “You should stop now!” she announces. They suggest possible narratives for the scene. Later, as I draw the unraveling of the linen edges with a fine brush and liquid sepia paint, I discover just as much dramatic tension in the story of the material’s decay as in the colorful characters woven into it.

Head and Shoulders, 2019

Acrylic on canvas

79 x 45 inches (200.5 x 114.5 cm)

Head & Shoulders: Cilla tells me that the subject is a clavus, the bright woolen decorative strip running over the shoulders of a linen tunic. And yet, when I first saw this textile on the table at the Bode Museum, it looked like a wobbly head, neck, and upper torso. It reminded me of a brutish figure by Dubuffet. “Head & Shoulders” is the name of a shampoo brand, and such irreverent imagery seems to deserve the title. A visitor to my studio stands in front of the partially painted canvas and asks if he is seeing an actual tapestry. I find this funny. I think I am painting cartoon representations of

stitches. The repeated lozenge shape—each described with a thin loose brush and each slightly different—is a cipher for bundled weft yarn. I paint the action of a strand that seems to jump, dolphin-like, up and over the warp thread to dive back under again. According to Thelma, some of the Late Antique imagery was intended to be silly and irreverent and even bawdy. What is happening in the little vignettes along the length of the body? I can’t help seeing the cartoon character, Bart Simpson. It looks like two figures, one perhaps across the knees of the other. They look to me like spanking scenes. Betsy has written about the “playful eroticism” in Late Antique textiles. I have permission to use my imagination. I have permission to laugh out loud in the studio.

Leviathan, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

60 x 92 ½ inches (152.5 x 235 cm)

Leviathan: Over the many months I spend exploring the topology of each subject with near microscopic intensity, I form an intimate relationship with it. As I study the structure and make creative errors in interpretation along the way, I give them affectionate nicknames. Leviathan was one of those. I look at what is in front of me, and what I see is a great open-mouthed whale. The subject textile is a fragment of a

child’s tunic, something I only learn from Betsy after I have nearly finished the painting. I follow the advice of Leonardo who encouraged artists to play the game of seeing figures and animals in clouds and other amorphous forms. In today’s letter Cilla reminds me that “Textiles are more closely connected to the human being than any other object.” This leads me to think of the child who wore this garment. Did she die young and was she buried with it? Perhaps she would

like that I have turned her little tunic into a sea monster.

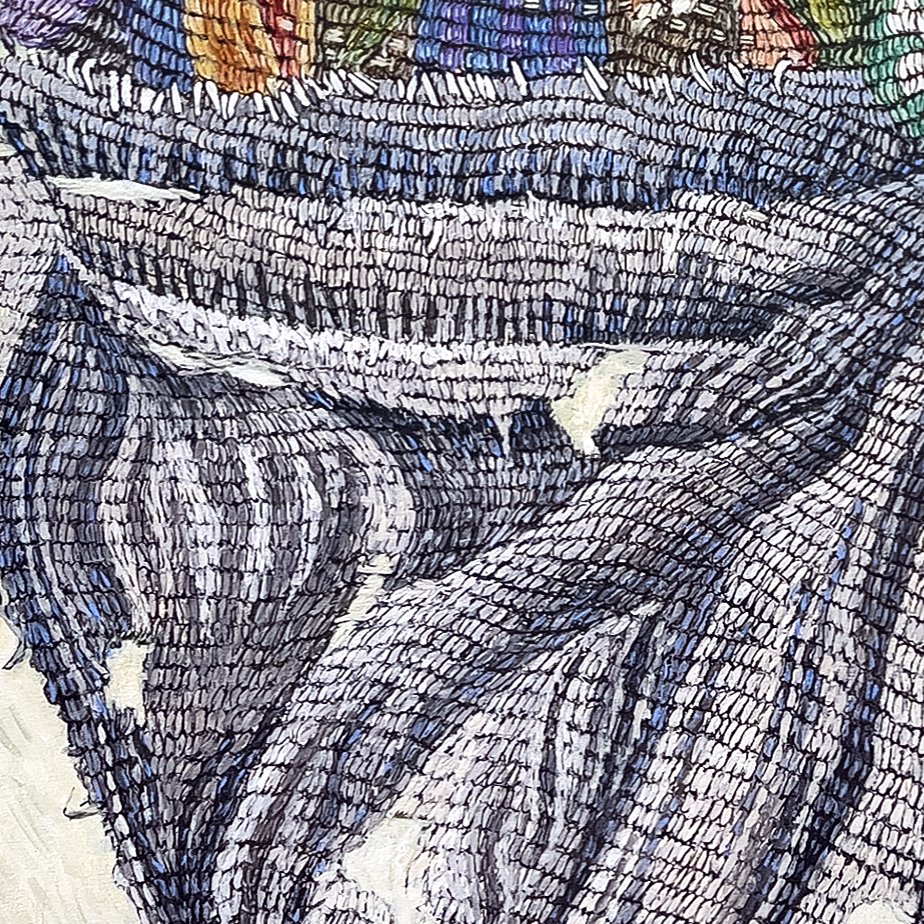

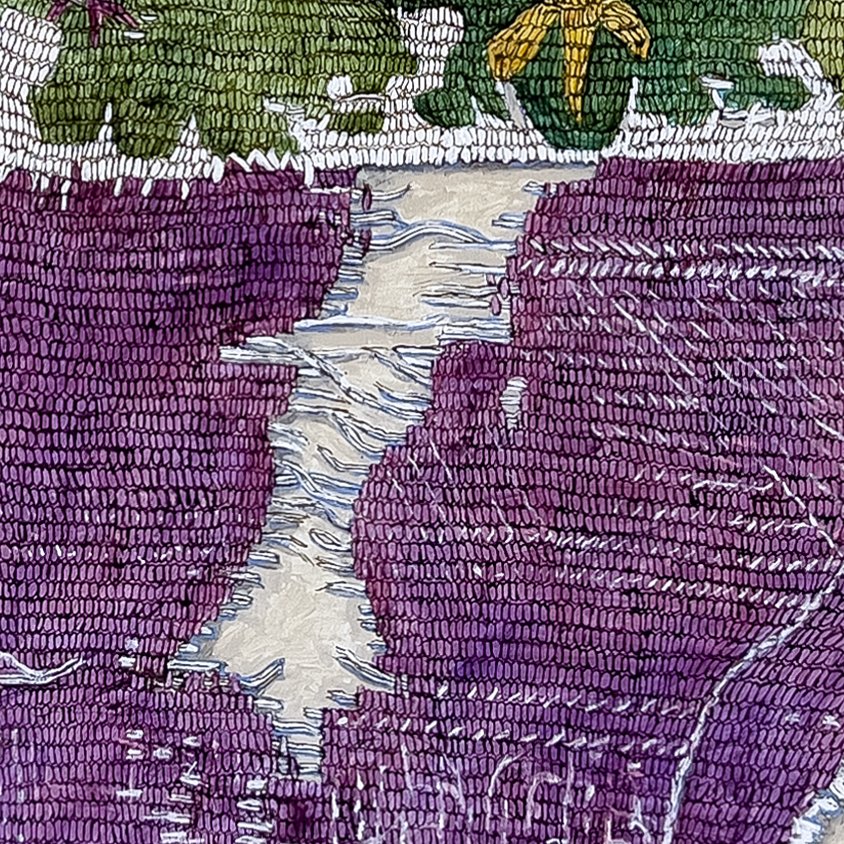

Vanitas, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

66 x 56 inches (167.75 x 142.25 cm)

Vanitas: It’s hard to believe that the glowing purples and greens are in such vibrant condition after being buried for over a thousand years. A painting of inanimate objects is usually called a still life. But I experience this lively bit of ancient fabric as quite animate. So, I call my painting a portrait. This particular tapestry fragment offers an unusual subject for me because, instead of representing humans and animals, it shows a bowl of fruit, which is a classic subject for

a still life painting. I unroll Vanitas for my friends at the Bode Museum. It is 10 March 2020, and everyone crowds around for a close look at what I’ve been working on for the last year. Although they’ve seen plenty of photographs, Cilla and Kathrin are startled by the scale of the actual artwork. Much of Western portrait painting is devoted to the detailed description of fabrics: rich satins and laces to code status and wealth. The last time I stood in the Velasquez room at the Prado among the stern-faced Spanish royalty, I was struck by how much space is devoted to the bravura depiction of fabric and how little to human flesh. A vanitas painting is usually a still life intended to remind the viewer of the transiency of human existence. It often shows rotting vegetation to symbolize the inevitability of death. When I zoom in on a corner of this textile, I am amazed to discover what looks like a Hamlet-like skull, seeming to grin

back at me from the loosening threads, Vanitas indeed.

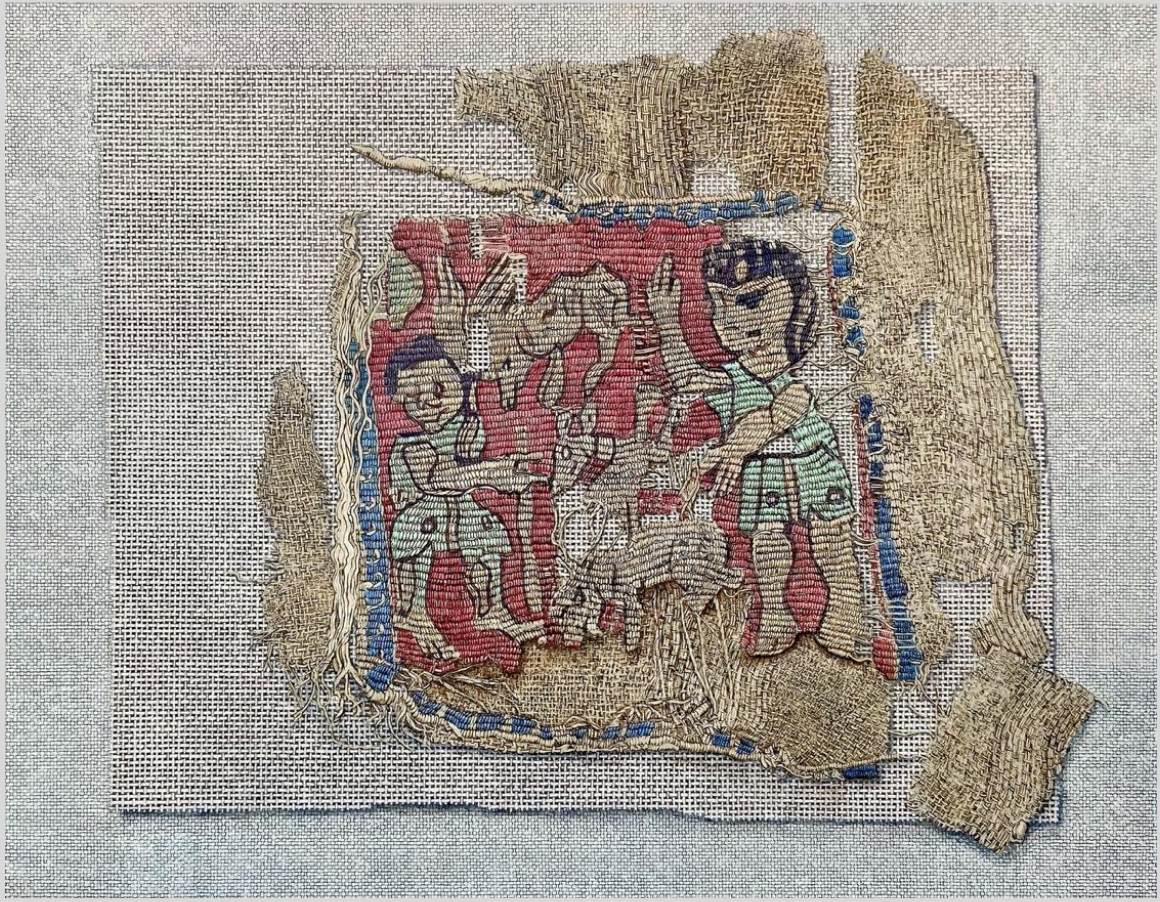

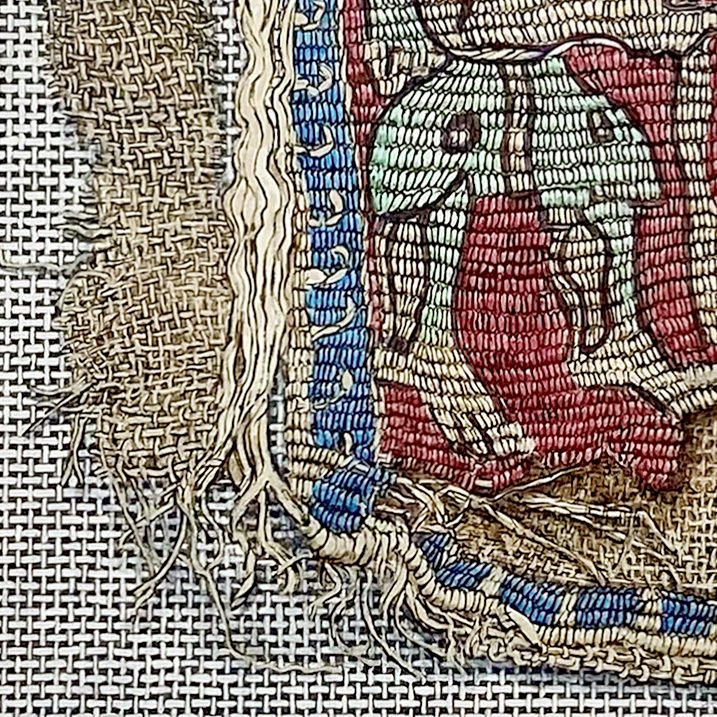

Unravellings, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

69 ½ x 62 inches (176.75 x 157.5 cm)

Unravellings: This is my first pandemic painting. After our trip to the Bode Museum in March 2020, Sam and I hurry back to the US amid threats of lockdowns with Vanitas wrapped carefully in a ski bag. I had discovered new treasures during this second visit to the Bode Museum and am eager to start painting them. There were two textiles we had examined in the Bode’s back room, both in deliciously degraded condition and both appearing to represent people and animals. Peering closely with Kathrin, I was struck by the difference in texture and regularity of the threads between that of the decaying hand-woven textile and the modern machine-woven background. She showed me how she had carefully and nearly invisibly stitched the fragile artifact to its mounting cloth. With a lot of time stretching before me and nowhere to go, it seems like an enticingly complex idea to explore. Can I even find a graphic language to interpret the irregular geometry of the black-and-white machine-woven background?

I arrive back home to a changed world and a very long quarantine ahead. After 35 years, I leave Brooklyn and relocate to the woods of Northwest Connecticut. Weeks become months and I find complexity and solace in this ancient fabric. The sweep of warp threads on the right-side figure appears as a wind-blown skirt. The weaver may not have dressed this shepherd in a bustier, but in its current condition that’s what I see. Outside my studio window there is a fox drinking lazily from the pond, so different from my former urban life. I paint the layers of beige linen, imagining them peeling back like a curtain to reveal multiple strata—a sort of geology. At some point I shut down the image on the screen and become lost in an intricate landscape of my own invention.

Bad Hair Day, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

87 x 40 inches (221 x 101.5 cm)

Bad Hair Day: This fragment teases with an elusive heraldic narrative. Let’s see: There seem to be a pair of lions facing each other. Or are they dogs? There are two more of them below. They certainly have impressive claws, so I say lion. What is the figure on horseback doing? Is he a knight? It looks to me like he is combing his hair with either a sword or a banana. He is holding something like a shield before him. I think it is a magic mirror in which a disembodied hand gives him an emphatic “thumbs down.” It seems to be saying that the knight’s efforts at grooming are not working very well and “you are having a ‘bad hair day,’ dude.” And then there is the disembodied head behind the horse’s rear end. What happened there? Did the knight execute someone for insulting his coiffure? Or is it his squire and the body is hidden behind the cipher of the horse’s tail?

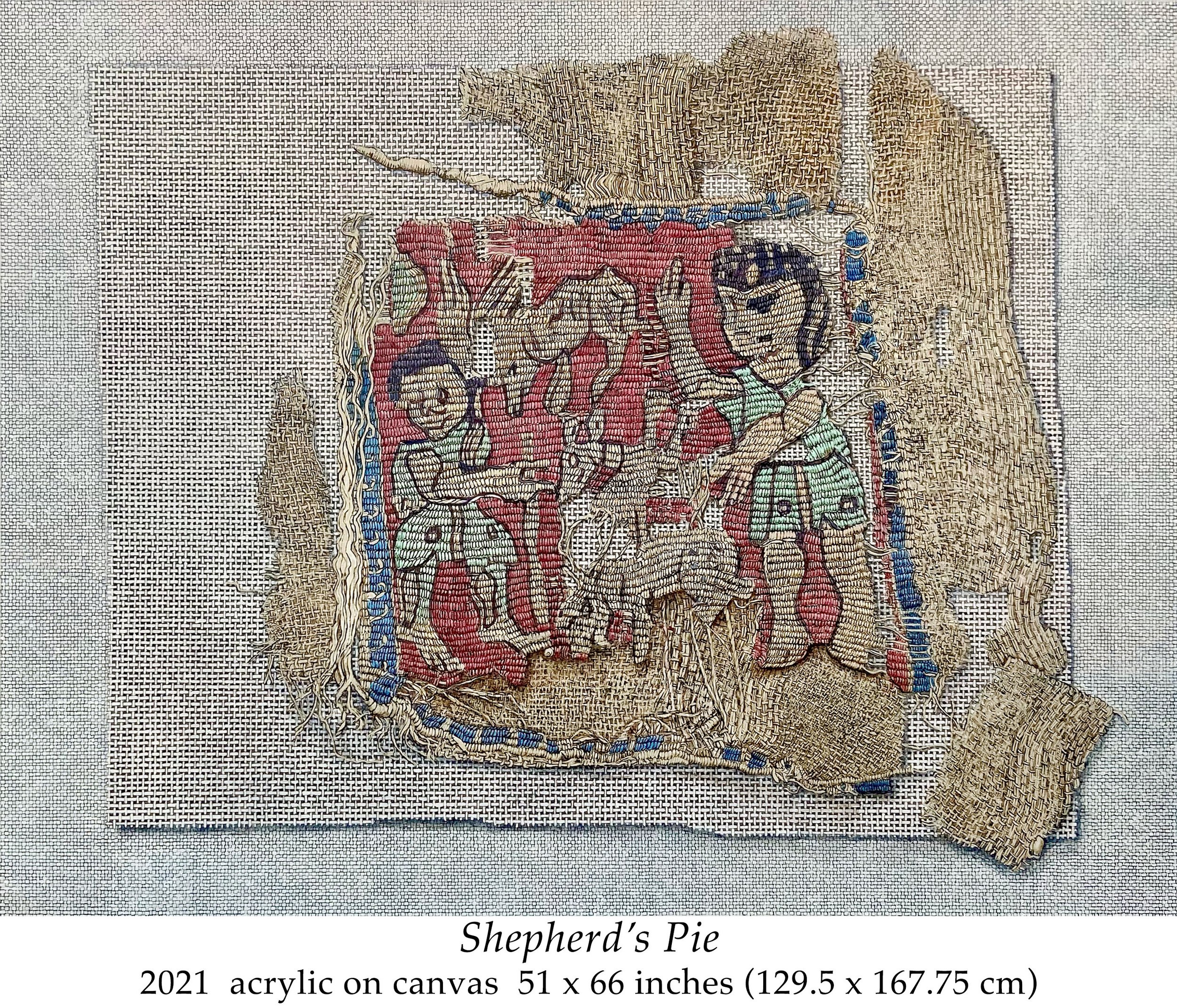

Shepherd’s Pie, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

51 x 66 inches (129.5 x 167.75 cm)

Shepherd’s Pie: I write to Cilla to ask, “Can you tell me more about the iconography in this piece? Are the two figures shepherds? I originally assumed so, but now looking at the wolf-like (and maybe dead?) animals at top and bottom, I wonder if they are hunters?”

“I like this sort of detective work!!!” she answers. “I still have a little preference for the shepherds, but let me think about it and look for more parallels. I’ll attach one from the Brooklyn Museum, which could be the clue to interpret our fragment.” I try to think of a more dignified title for this painting, but the brushwork is serious enough. The image is broken up, and the figures in their short green tunics are certainly odd. How much of this distortion was intended, and how much has time created? One Sunday evening over a long-distance glass of wine, Thelma and I joke about the poor fellow on the left and dub him the village idiot. We laugh, imagining that the shepherd on the right is gesturing to the sky in frustration at having to spend yet another day in the company of this simpleton with the squashed face. A “shepherd’s pie” is a minced meat dish covered with a layer of mashed potatoes.

I wonder if I can take the juxtaposition of machine-woven fabric and ancient hand-woven fabric even further than I had in Unravellings or Bad Hair Day? This sets up a real technical challenge since there are two layers of contemporary fabric. Corresponding with my helpful friends is a welcome relief to the isolation. “How kind of Thelma to share my Dumbarton Oaks article with you.” Kathrin Colburn writes from New York City which, during the pandemic, seems as far away as Berlin. “I am impressed that you picked up on the paired warp threads. Not much escapes your eyes when examining these pieces up close—even all the later interventions. It is great.”

Snow is falling, and the hours of sunlight during which my pigments glow are so few. In the evening when I put down my brush, I still see the regular geometry of stitches beneath my closed eyelids.

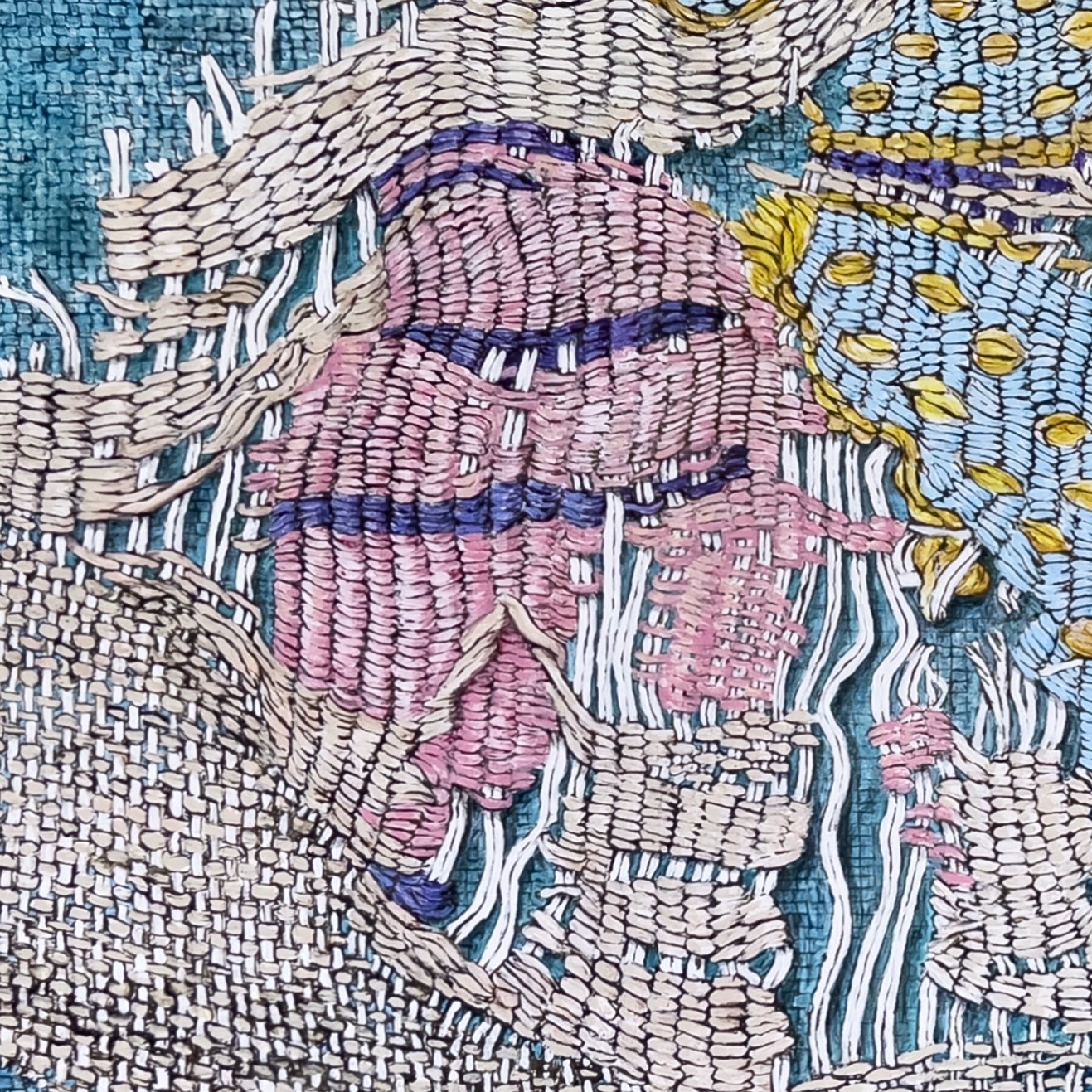

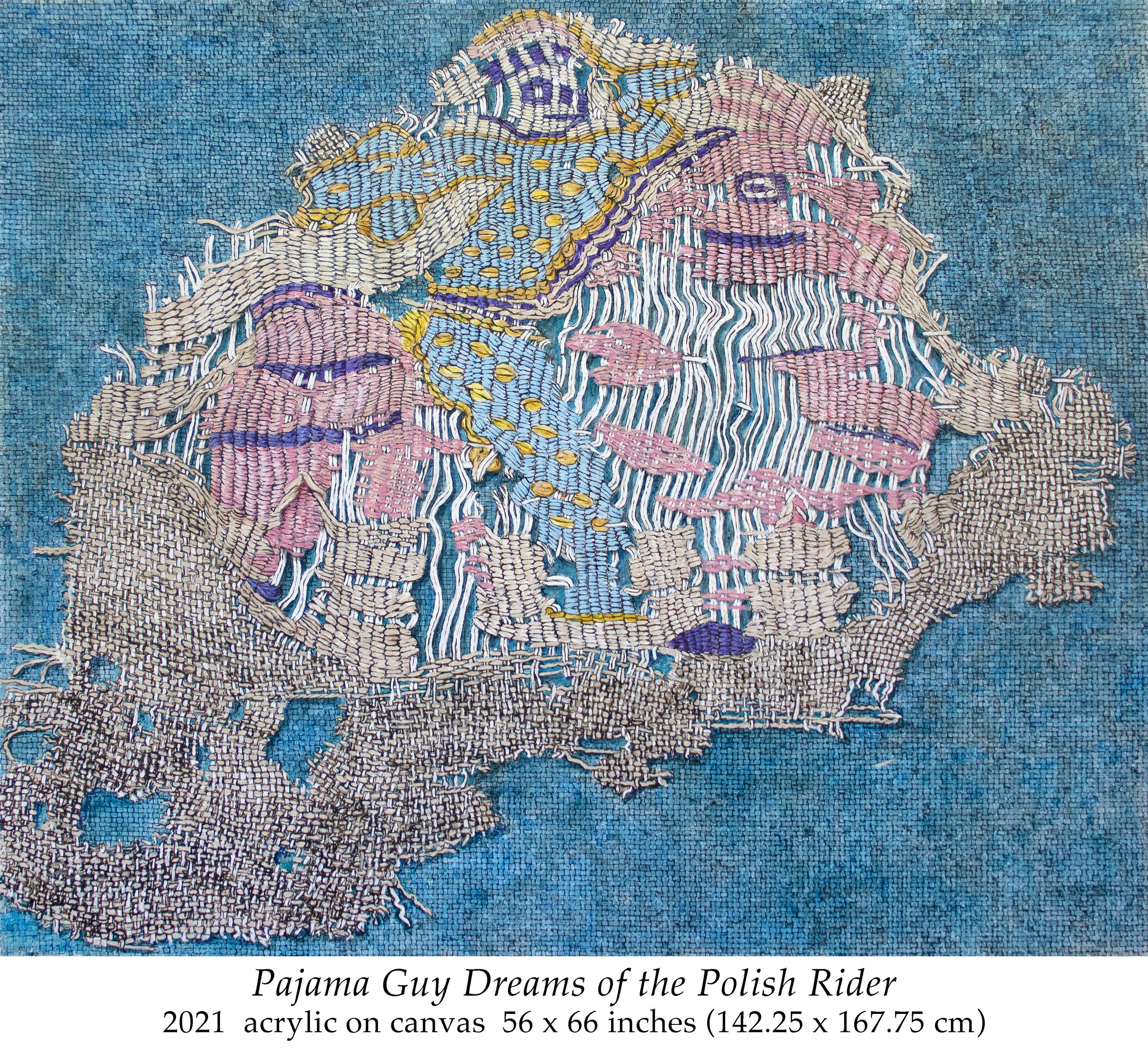

Pajama Guy Dreams of the Polish Rider, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

55 ½ x 62 inches (141 x 157.5 cm)

Pajama Guy Dreams of the Polish Rider: Wavy white warp threads exposed over time have left small fluffy islands of pink wool weft. That was my first impression of this fragment. And doesn’t the broken-up horse look like one of Boccioni’s figures in motion? The rider is wearing a yellow-on-blue polka dot costume that Thelma and I agree look like pajamas. Painting the yellow spots and allowing them to become the lemons they want to be, I have a feeling I’ve seen this fellow somewhere before. One day it hits me: Rembrandt’s The Polish Rider that I have admired so often at the Frick Collection in New York is riding in much the same long-stirrup posture. Maybe Pajama Guy is a rodeo clown? As I paint the teal of the background mounting fabric, it starts to remind me more and more of pharaonic faience. I follow that instinct and allow the glazes to make the textile look almost like mosaic or glazed ceramic. Now I know what the background of Bad Hair Day really needs. This is the ninth and final painting for the exhibition. It is hard to believe that I have been working on this series for three years. The way I see the textiles and the painting language they have demanded of me have evolved over that time. I select different subjects now than I might have in the beginning.

“Dearest Cilla,” I write, “This painting is truly the culmination of my study of your collection. I had to repaint and re-think the transition from tapestry to plain weave several times before I understood that the doubled warp threads in the tapestry weave split into single threads in the plain weave. Making this must have been an incredible tour-de-force! The result of all that re-working is that the plain-weave section has a particular energy and life. The background buckram is painted with layers of glazes and is really luminous. I can’t wait to see how it shines at the Bode! And, finally, make sure that Kathrin sees how I located most of her tiny stitches and celebrated them in the painting! Sam always says I talk too much, and I should just let people use their eyes and see the painting. But you can tell how excited I am!”