German National Textile Museum Krefeld Exhibition 2022

August 21st, 2022 - April 2023

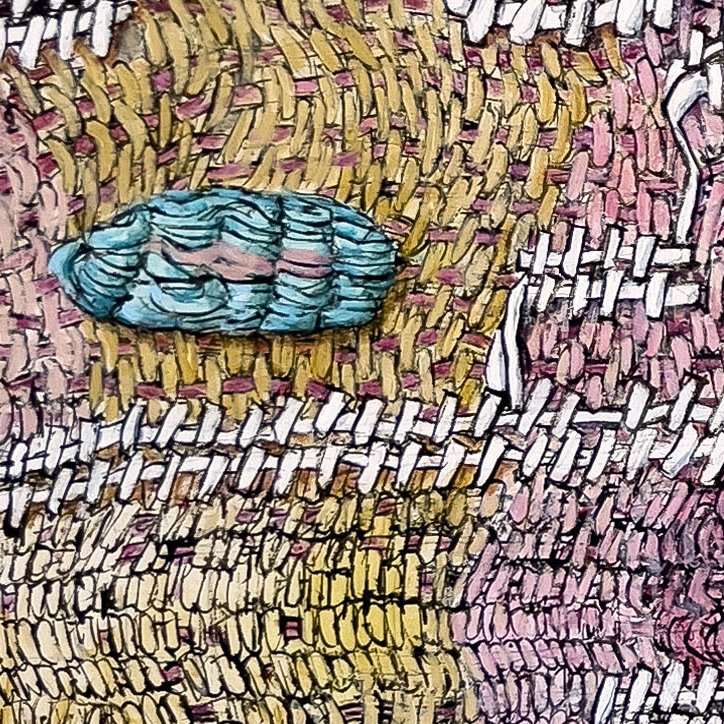

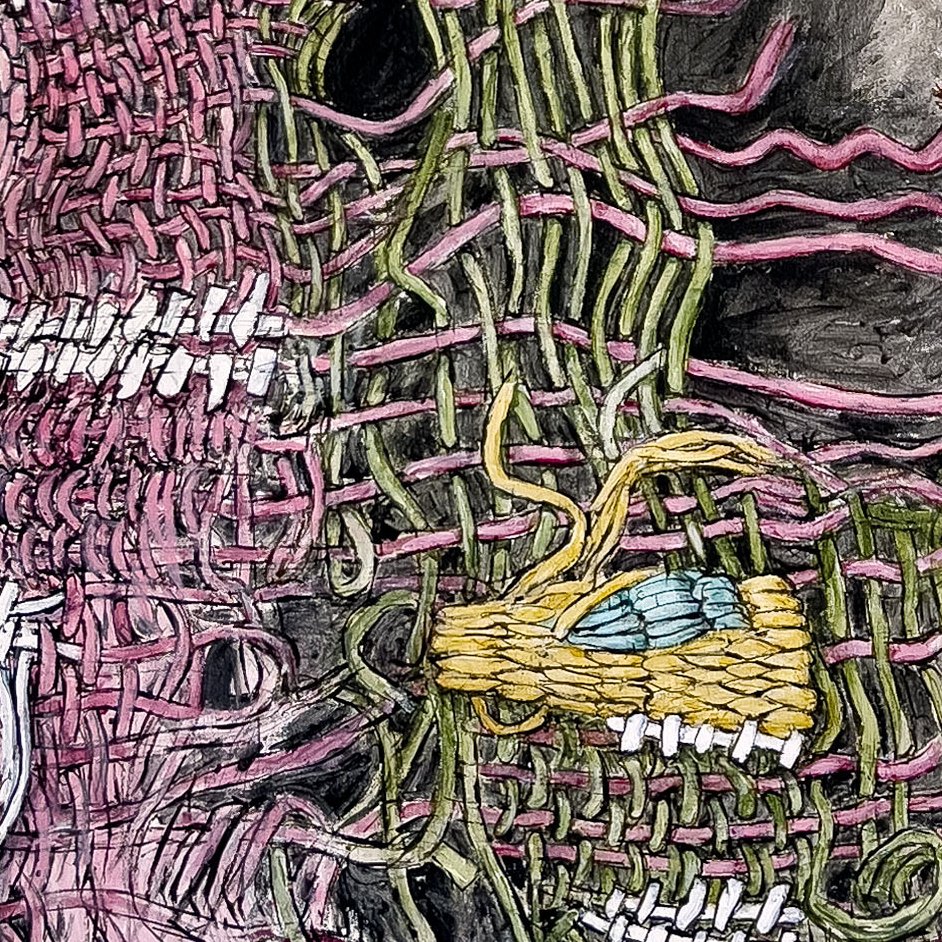

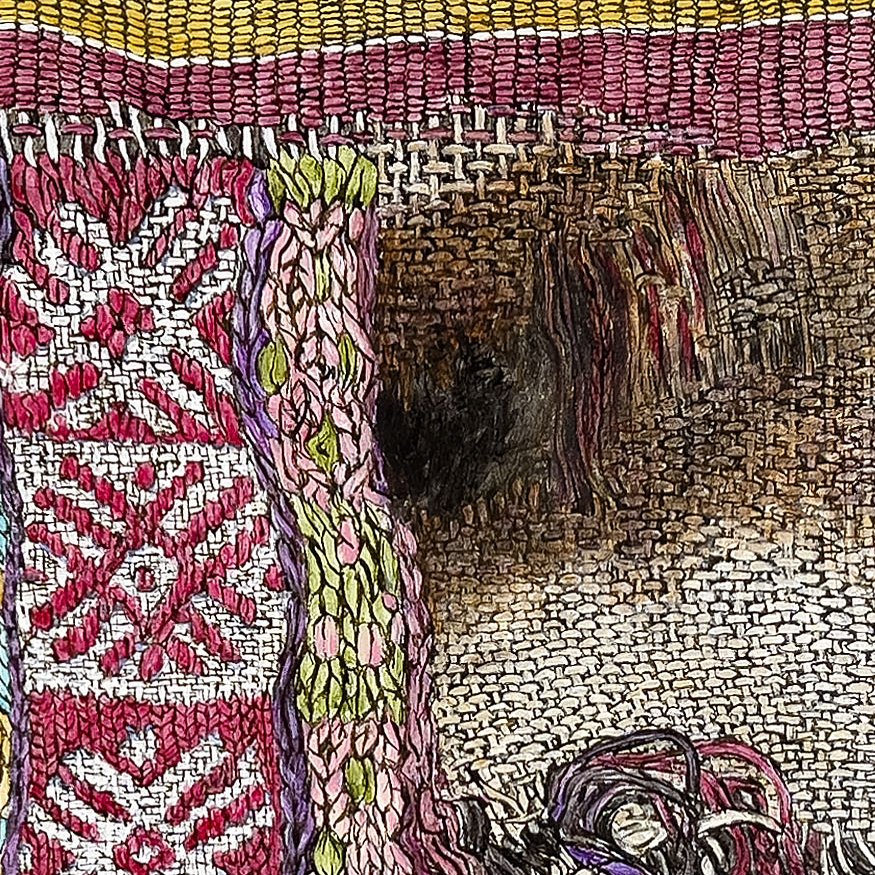

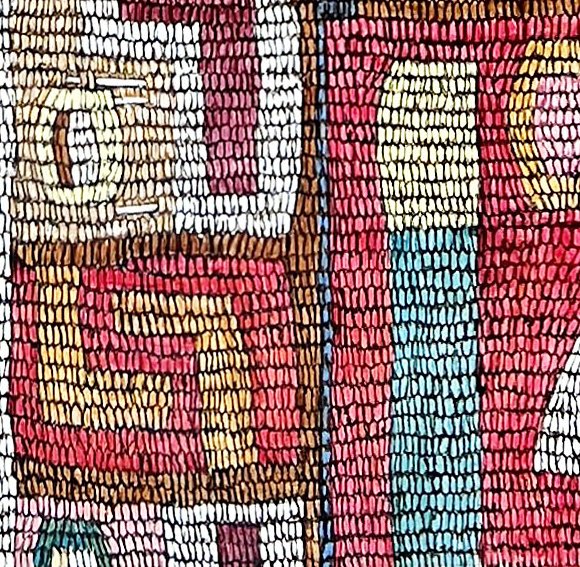

An exhibition including Rothschild’s portraits of Pre-Columbian weaving from ancient Peru

opens at the German National Textile Museum in Krefeld in August 2022 and continues to April 2023

Read reviews of the show here:

Gail Rothschild talks about her inspiration for her works in the German Textile Museum Krefeld’s show Peru- Ein Katzensprung

Catalogue Essay: On Painting Homages to Wari Weaving

By Gail Rothschild

The year I entered Yale College, 1976, was the year Josef Albers died, but his influence could still be felt throughout the school. I stood squinting before his Homage to the Square paintings at the Yale University Art Gallery lost in their optical play of space. When I began my portrait of the Wari tunic from the collection of the German Textile Museum, I discovered within it what looked like an exercise right out of Josef’s Interaction of Color: “As a practical study we ask that two small rectangles of the same color and the same size be placed on large grounds of very different color.”

Anni Albers had not intended to become a weaver, but the Bauhaus had sexist notions about what women could and could not do, and so she was pushed, against her will at first, to join the weaving workshop. Years later, she would share her theories about the “pliable plane” of textiles with architecture students at Yale. How I wish I had known her when we were toiling in separate Connecticut studios just a few miles apart. The first women had only been allowed to enter Yale College as undergraduates in 1969, and I searched for female guides through what was still a male-dominated school. My introduction to this great teacher/weaver/theorist came through a friend, the art historian, T’ai Smith, who has written insightfully about Bauhaus weaving theory and about my Portraits of Ancient Linen.

Anni invited her students to literally pick apart small fragments of Mesoamerican textiles to figure out their construction. I am not a weaver like Anni. Instead, I investigate the structure of ancient weavings through paint, exploring how they were made and how time is un-making them.

If you take a deep dive into the world of historic textiles, as I have, it is easy to forget that this material remains an underrated, gendered medium and devalued as women’s work. While some contemporary artists challenge this prejudice through the subversive use of fabric and needlework, I choose to do so by making paintings on canvas of textiles—heroically scaled paintings that celebrate fragile remnants of the past.

By the time Anni and Josef met at the Bauhaus in 1920s Berlin, the Museum für Völkerkunde had the largest collection of Andean textiles in Europe. We know for sure that Anni frequently visited, but I like to imagine the two of them hand-in-hand studying the rectangles of bright color and learning form and structure from first millennium master artists.

As I delve deeper into these Andean textiles, I feel Josef looking over one shoulder and Anni looking over the other. Josef points out that the Naples yellow rectangle within the Phthalo blue one isn’t quite right, while Anni reminds me that “a painted face obeys other laws of formation than a woven face.” “But Anni,” I insist, “my subject IS a woven face!” Searching out the complex interaction of threads in the subject gives an order to my process. “Limitlessness,” Anni reminds me, “leads to nothing but formlessness, a melting into nowhere.”

Perhaps all geometry begins with the grid of the loom and the intersection of warp and weft threads. Whether I like it or not, geometry pervades my work. I use it. I embrace it. And (sorry Josef) I resist it. Each painting begins by gridding a canvas and lettering each box. It is not lost on me that I amthus setting up a kind of loom. The Wari told their stories through abstracted human and animal symbols. In my portrait of an ancient Andean textile, the taut geometry has softened, relaxing over time as threads have unraveled. This fabric once communicated complex ideas about society and personal identity, but it has long outlived its makers and its meaning. We who privilege written language over images, cannot decipher the message in a Wari cloth.

Although I have seen Andean textiles in other museum collections, I know the three subjects for my portraits in this exhibition through digital images on the internet. I’ve never been to South America; yet I collaborate with the Peruvian archaeologist Rommel Angeles Falcón, working from detailed high-resolution images he has generously shared from Huaca Malena. The resulting two paintings, Black Holeand Esquina Decorada, imagine new narratives for these artifacts.

In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin observes that photography “substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence.” Even as he celebrates photography’s ability to make art available beyond an elite few, he also mourns the loss of the work’s “aura,” its “unique existence where it happens to be.” The artifact’s “aura,” Benjamin would say, is missing from the photographic close-up I study while making a painting. The challenge for me is to invest the canvas with the magic I attribute to the original object.

From their many trips to Mexico and South America, Anni and Josef brought back samples of the Pre-Columbian art they loved, keeping them at hand in a basement cabinet. But the inspiration for my paintings comes via photographs, and I accept that most people see my paintings via digital images on a screen. My iPad is speckled with paint because I zoom in on details of twisted and linked threads. This dissection endears my paintings to textile conservators and art historians who also journey slowly across thelandscape of the fabric that only under the microscope reveals its mesas and huecos, mountains and plateaus.

My relationship with Pre-Columbian textiles takes place through museums and their digital extensions. The fragments I am drawn to show their ageand so are often not the ones selected for museum display. I am aware that what I see is the result of active decisions on the part of archaeologists, dealers, curators, and conservators. The deterioration of the fabric has been arrested—if only temporarily in the greater scheme of time—each thread held in suspended animation.

I have more experience painting portraits of the “Coptic” textiles of Late Antiquity. But Anni showed me that at the same time and across the world from Egypt, Andean artists were employing similar tapestry techniques. In her book, On Weaving, Anni celebrates both Late Antique Egyptian and Andean textiles as true “works of art” that never seek to hide their structure, preferring them to Western tapestries that are simply woven versions of paintings. As someone who paints homages to textiles, I find this to be a provocative idea.

Maybe it’s the rock-climber in me, maybe it’s the former sculptor, but I am more concerned with the haptic than the optic, leaning more toward Anni than Josef. “We touch things to assure ourselves of reality,” Anni wrote, “We touch the objects of our love. We touch the things we form.” Since I cannot handle the ancient textiles, my brush must invent pliability and movement, carving out a muscular reality on a two-dimensional plane.

Because my subjects were buried in a dry climate for centuries, they retain much of their vibrant color. I can’t help but be seduced. Once again, I pull Josef’sInteraction of Color off my bookshelf. “Good teaching”, he reminds me, “is more a giving of right questions than a giving of right answers.” I smile as I brush another layer of Alizarin Crimson glaze over Naphthol Red. I am curious about the rich dyes the Andean artists made from plants and insects. In the studio, I respondto the relationships of these dyes using synthetic pigments. I ask Josef and Anni if they appreciate the irony. The weavers’ dyes penetrated the fibers of alpaca wool becoming part of them, while the pigment from my brush sits upon the white-grounded surface of a mechanically woven canvas.

These are all paintings about time and the process of decay. Each fragment of textile has a history. I imagine the alpaca whose wool was shorn; the cochineal insect whose body produced the bright red dye; the weavers; and the users of these textiles, who were buried with them. Color is fugitive. Life is too. The process is only temporarily halted. Without question, these tenacious textiles are worthy subjects of portraiture.